An Upcoming Book that Examines the Frenzied Interrelationship Between Art and Violence

by David E. Gussak, PhD, ATR-BC

In March 2022, Oxford University Press will release The Frenzied Dance of Art and

Violence, my latest–and likely my last–book. A culmination of 8 years of work, this book will

explore what I believe to be the inextricable interrelationship between art and violence.

As an art therapist for thirty years who specializes with forensic populations, I have held

an unwavering conviction that the impulses and forces that drive violence and aggression may be

the same that drive one to create. Historically, many well-known artists have demonstrated

volatile, aggressive, violent—and sometimes even murderous–tendencies. It seemed to me that

those artists inclined towards violence–such as Caravaggio, Cellini and Dali– channeled these

destructive forces into their art. Some have created despite–or because of — overwhelming

societal conflict and violence that surrounded them, such as Goya, Beckmann. Picasso and Vann

Nath. Such creators used their art to help them make sense of, or gain power over their violent

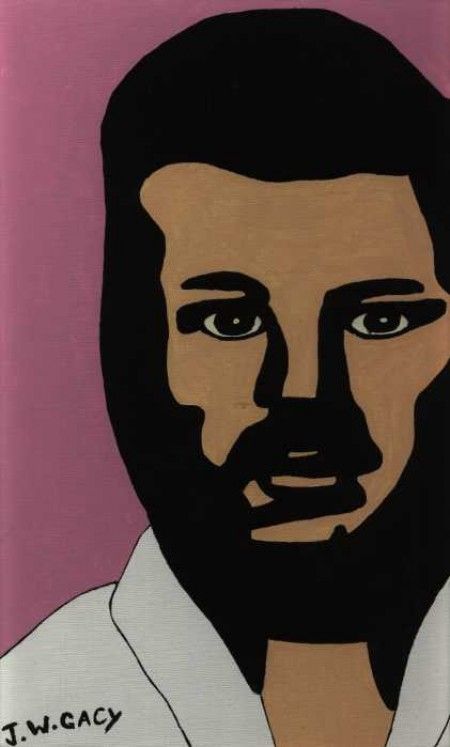

circumstances. A number of heinous serial killers and multiple murderers drew and painted

works that society finds repelling and compelling. Yet it seemed that these atrocious offenders–

like John Wayne Gacy, Richard Ramirez, Charles Manson and Adolf Hitler– may have wielded

drawing and painting as a weapon, to mirror, even continue their psychopathic cycles. The in-

depth essays that make up The Frenzied Dance explores these disparate and numerous elements

to reveal and clarify these various interrelationships between art and violence.

The Dance Begins

In 2012 I was in the final stages of my book Art on Trial about my experiences

testifying as an expert witness on the drawings and paintings completed by a man being tried

for the murder of his child. During one of the many conversations with my publisher I told her

about lectures I recently gave in Las Vegas on paintings by the monstrous serial killer, John

Wayne Gacy.

John Wayne Gacy 1 (b. 1942; executed 1994). Self- Portrait (Date unkn.). Oil on canvas board. Permission provided by Jim Taranto.

John Wayne Gacy (b. 1942; executed 1994). Death of Pogo (Date unkn.). Oil on canvas board. Permission provided by Jim Taranto.

She was fascinated. Indeed, she was surprised –as many people are–to learn that a

number serial killers have drawn and painted. As a result, and as any good publisher might, she

saw a book in this. She suggested that perhaps my next project could focus on the art of serial

killers. While I was averse to providing a single book on what I felt could merely be a

voyeuristic endeavor, a seed was planted, one that would grow into something well beyond the

paintings of such multiple murderers. I was compelled, almost driven, to go beyond this prurient

examination, to discover and deeply explore the potentially explosive and dynamic

interrelationship between art and violence.

Charles Bronson/Charles Salvador (b. 1952). Bronson- 1314- LIFE (2004). Pencils, colored pencils, and ink on paper. Permission provided by the artist.

I gained further insight into the phenomena of murderabilia after connecting with a

Berlin-based collector of the art of serial killers. And through it all I met with clinicians,

sociologists and artists for their insights and perspectives. From all this, I began to conceive of

this dance.

Just what kind of Dance is this?

At first, I saw this interrelationship as a tango; a constant, vigorous interplay between two

entities, one leading, the other following, then switching directions. Yet, the original premise

was built on the assumption that there were only two movements – violent energy driving the art

and art turning aside the violence. In my vision, sometimes art would lead and then sometimes

violence would; their interplay would remain harmonious.

Yet it gradually became clear that this was simply not the case. Despite my best efforts,

the idea of it being a symphonic dance did not hold up at all during the years of research and

writing; what emerged was something much more complicated.

As the chapters evolved, I began to realize just how convoluted this interrelationship

really is. While in some ways what I uncovered seemed to strengthen my already existing

beliefs, in other ways new insights replaced previously held assumptions. My original vision

began to shift, different truisms made themselves apparent, and a different project than originally

envisioned evolved. This dance was not held between two entities–it was amongst several

forces, perhaps changing partners, perhaps changing directions, perhaps all dancing together,

frantically, with great deal of fervor.

Indeed, art does seem to result from the same drives as aggression. It seemed the same

libidinal and narcissistically-driven forces that compelled Caravaggio to murder, Cellini to rape,

and Dali to assault, was the same energy that drove them to create incredible bodies of work.

Still, others suffered from inner demons whose control was impeded by alcohol, narcotics

or neurological impairments, that when combined with their own anxieties, doubt and unresolved

neuroses, resulted in uncontrollably volatile actions. For people like Pollock, Modigliani and

Dadd, who’s aggressive acts may have been instigated by such impediments, art seemed to

provide an effective–albeit brief at times– means to contain and redirect these impulses.

Even still, for all of the artists included in this text, their proclivities did not occur in a

vacuum: in many cases, they were further informed, driven, and even encouraged by the social

and political contexts of the times in which they lived and created. Yet, regardless of where the

aggression and violence derived, the artists’ creativity seemed to be fed from their libidinal and

aggressive drives, which, in turn, could diminish or even assuage their destructive tendencies.

Simultaneously, their art may have resulted from their need to cathart, sublimate, or contain their

aggressive inclinations.

In other words, their art was a way to wrestle with and even cage their hidden demons.

In many cases, art seemed to provide a means to regain control, re-humanize, re-

empower, maybe even escape for those affected by societal and cultural violence. There are

those like Picasso, Goya and Beckmann who illustrated the horrors of what they saw as a means

to make sense of it, to bear witness of the atrocities as a warning of what we are capable of. For

those who were unwilling pawns and the targeted sufferers of war such as Nussbaum and Vann

Nath, art provided a way to take back the control that was so violently snatched from them– to

lift them above their destructive, dehumanizing victimization while providing evidence of what

had befallen them. Even still, artists experiencing civil exploitation and volatility, either as

sufferer–such as Bill Traylor–or witness–like Norman Rockwell, used their talent as the only

weapon they had to stand up, fight back, and maintain their own identity and integrity.

However, when I began to deeply examine the disturbing histories and drawings of the

multiple murderers and serial killers, I was stumped. In full disclosure, these examinations

remained some of the most difficult to write as I tried to balance respect for what we can learn

from these perpetrators while not glorifying them. I had to examine my own desire to write about

them which I knew might still excite a certain subset of readers. Simultaneously, as I became

more embedded in these murderers’ backgrounds, I found I was oscillating between

desensitizing myself to their horrors and becoming overwhelmed, depressed, and anxious about

the inhuman nature of their crimes. It was also confusing; unlike many of my clients and the

artists presented earlier, it seems that these men would not nor could not benefit from the art

making: in fact, the work they produced and what it represented for them shattered my

previously held beliefs on the benefits of art making for those who are violent and aggressive.

Lee Boyd Malvo (b. 1985; remains incarcerated). The Prison Well Made by Mind (Date unk.). Pencil, ink on paper. Collection of Mirko K. Permission and reproduction provided by from Mirko K.

Glen Edward Rogers (b. 1962; remains on Death Row). Untitled (Date unkn.). Colored pencil on paper. Collection of Mirko K. Permission and reproduction provided by Mirko K.

Charles Manson (b. 1934; died 2017 of natural causes in prison). Shoes (Date unkn.). Oil on canvas board. Collection of Ken Dickerson. Permission and reproduction provided by Ken Dickerson.

Most of them did not begin drawing and painting until they were already arrested and in

prison for their heinous acts. Taking advantage of society’s fascination with such artefacts–with

murderabilia–they made sure that they remained visible to others. None of them seemed to

channel their violence and murderous ways through the art nor did the art seem to turn aside their

violence. Actually, what seemed to emerge was that the art was used as a weapon once they were

imprisoned to continue and perpetuate their wanton destructive patterns and reinforce their

narcissistic cycles from whence their violence originated. Once this realization materialized, it

became clear that I could no longer imagine it as a simple dance made up of two partners.

This realization informed my ability to deconstruct the enormous differences between the

opposing sides of one particular global atrocity, The Holocaust. On one side is arguably the

worst multiple murderer of all time, Adolf Hitler. As a painter, he engaged in his own

narcissistically-driven, dispassionate endeavors; as a ruthless dictator, he used art as a weapon

against his targets. Then there are those who suffered at the hands of the Third Reich. These

artists demonstrated remarkable evidentiary and rehumanizing creations. The comparison lays

bare the stark disparities, emphasizing the vast distance between inhumanity and humanity

through works that emerged from aggressive self- aggrandizement and the art that was birthed

from the desire to be seen and made whole.

All of this culminated in revealing the vast array of how art may be used to pursue peace,

reconstruct new identities and redirect and overcome aggressive and violent energy. Ultimately,

in short, how creating can facilitate change–through spontaneous art making, art education, and–of course–art therapy.

Through all this, a new overarching perspective became abundantly clear; no longer

could the image of a simple dance made up of two partners capture the complexity of this

interrelationship between art and violence. It is much messier, frenzied, feverish, and chaotic.

Perhaps a tarantella?

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, as I concluded in the Epilogue, in the process of researching for, reflecting on,

and writing this book, two seemingly antithetical and counterintuitive notions emerged:

- Aggressive and violent impulses are not always bad

- Art making is not always good.

Many of society’s laws and therapeutic interventions seem to be built off the premise that

aggression and violence are to be avoided or eradicated. This is easy to understand. My primary

experiences have been with violent offenders whose very actions have been crimes against

people and property, often because of misdirected impulses. Inherent in these systems is the

propensity to place negative and long-lasting labels on those that engage in such tendencies.

What has naturally emerged is the common belief that violent expression and aggressive

impulses are destructive and counter-productive.

Some examples illustrated in several of these chapters provided scenarios in which

violence was indeed detrimental to themselves and others. For example the actions of the

multiple murderers and some of the established artists like Caravaggio, Cellini and Dali. They

demonstrated how unchecked actions emerging from narcissistic cycles can be harmful and

dangerous. There are those whose destruction emerges from impulsive reactions to situations that

arose from diminished control due to substance use or neurological impairment such as Pollock,

Modigliani and Dadd.

However, as the book’s opening chapters argued, aggressive energy may also be a

valuable and beneficial force, from which change can occur and creative expression arise. Such

forces can and will contribute to actions that may overcome adversity and resolutely resist

limitations. Societal protest against injustice–such as the French Revolution, the Civil Rights

and Suffragist movements, or the recent Black Lives Matter– rely on aggressive pushback and

violent demonstrations to instigate change.

Artists such as Goya, Picasso and Beckmann relied on their aggressive and retaliatory

impulses against the injustices they witnessed and experienced to create monumental works of

expression. Rather than let the violence against them erase them from the world, those like Vann

Nath, Traylor, Nussbaum, Nowakowski and Haas used their art to fight back, with works that

would long outlive them. While not always socially acceptable they have been socially

productive. Aggressive energy, sometimes revealed either through impulsive or calculated

violent expression, becomes a drive, and when sublimated properly, can be instrumental for

change, development and creativity.

Guernica Children’s Peace Mural Project. Children of Tallahassee. Paint on canvas.

Permission and Reproduction provided by Dr. Tom Anderson.

On the other hand, art making is not always good. Recognizably, this runs counter to

beliefs that I have embraced and relied on since becoming an art therapist. Sometimes, art

making may not always be the balm that we would like it to be. It doesn’t magically transform

everything into good. Make no mistake. Art is never benign, innocuous or insignificant. It is a

powerful, potent and sometimes dangerous tool that can be used–to alleviate or magnify–

violence and aggression. Who uses this tool determines whether it is constructive or destructive.

Art is and remains an extension of the creator. As I indicated in a previous publication, for some

“art becomes the great equalizer, humanizing those that have been previously dehumanized.

Only when someone creates are they recognized as being alive”. Contrarily, for those who wish

it to be, art is a dangerous and malicious weapon.

Clearly, the examinations in this book are far from complete. There is much more

exploring and reflecting that can occur about the interrelationship between violence and the arts;

and not just visual art, but music, dance, writing and drama as well. Yet, I believe that as

preliminary conversation starters, these chapters have satisfied, informed and solidified my own

realization of the relationship between art and violence, and that there seems to exist a distinct

and clear interdependence and co-reliance between art and violence. Indeed, the messy, complex,

frenzied dance continues unabated.

One Final Note

While finishing this book, major changes began to occur around the United States and

the world. We were hit consecutively by violent and aggressive events that rocked the physical,

social and cultural fabrics of our nation– the advent of COVID-19 followed by the Black Lives

Matter movement. While neither were fully explored in this book, they both loomed large within my own psyche. Along with all of the fear, anxiety, helplessness and anger that global citizens

experienced were the creative responses that many of my colleagues and friends used to address

these violent upheavals. The power of art became apparent, providing various mechanisms to

address and adjust to the changes. Various forms of artistic expression were used to make sense

of all that was happening, escape from immediate anxiety and fear, and as a weapon against

injustice, ignorance and anger, while providing opportunities for burgeoning hope and

gathering strength.

While this book presents historical accounts, these events reminded me that the frenzied

dance never stops.

All images are borrowed from the upcoming publication, The Frenzied Dance of Art and Violence and

remain under copyright by the publisher and the author.

David E. Gussak, PhD, ATR-BC has been a Professor for the Florida State University’s Graduate Art Therapy Program for 20 years. He also helped develop and institute the FSU/FL Dept of Correction’s Art Therapy in Prisons program, for which he serves as its Project Coordinator. As an art therapist for almost 30 years, Dr. Gussak has presented and published extensively internationally and nationally on a number of topics, but most particularly on forensic art therapy and art therapy in forensic settings. Along with a number of journal articles, book chapters and edited volumes, he has also writtenArt on Trial (Columbia University Press, 2013) and Art and Art Therapy with the Imprisoned (Routledge, 2019).

He is also the co-editor, with Dr. Marcia Rosal, and contributing author for The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy (2015). He is currently on the editorial board for Art Therapy: The Journal of the American Art Therapy Association and Arts and Psychotherapy, as well as a guest editor for several other journals, including The International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. He lives here in Tallahassee with his wife Laurie and his son Joseph; his daughter lives in the great white North of Canada. After all this time, he still loves what he does, and still can’t believe that he gets paid to do it; still, despite this, given his distaste for writing, he stresses that The Frenzied Dance of Art and Violence (Oxford University press, 2022) is his final book. Really. He insists.